Ever since we got to Europe four years ago we had circled the gardens of Giverny as a bucket list go-to. With our journey in Europe coming to an end we decided to take a drive to Giverny and spend a couple of days in Monet’s gardens and visit the house where he created a new art form back in the early 20th century.

Giverny is about two miles away from the town of Vernon, a rather sleepy town located on a lazy part of the Seine river which flows through Paris and empties into the English Channel at the port city of Le Havre. We rented an apartment right on the banks of the river and woke up our first morning to a fog just lifting over the river. A perfect harbinger of what was to come.

Claude Monet, born Oscar-Claude Monet on November 14, 1840, in Paris, France, is widely regarded as one of the most influential painters in the history of art and a foundational figure in the development of Impressionism. Through his lifelong dedication to capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere, Monet redefined artistic expression and laid the groundwork for modern art. His journey was forever cemented when he purchased property in Giverny and created a library of artistic genius from the gardens he created.

Monet spent most of his childhood in Le Havre, a port city in Normandy, where his father worked as a grocer. Though his family hoped he would join the family business, Monet’s artistic talent and passion were evident from an early age. As a teenager, he gained local fame for his caricatures, which he sold for small sums. This early recognition encouraged him to pursue art seriously.

Monet began formal art training in 1859 when he moved to Paris. Rather than aligning with the rigid academic standards of the École des Beaux-Arts, he found inspiration among a new wave of artists experimenting with modern techniques. He studied informally under Charles Gleyre, where he met fellow painters Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Frédéric Bazille, and Alfred Sisley. These friendships were crucial, as they would later collaborate to create what would become the Impressionist movement.

Rejecting the classical themes and polished finishes of academic art, Monet and his contemporaries sought to depict the world as they saw it in the moment. They painted everyday scenes, landscapes, and people using rapid brushstrokes and bright, unmixed colors to reflect the changing quality of light. Monet especially was fascinated by how natural light shifted throughout the day and across seasons.

A key element of this new approach was en plein air painting—working outdoors rather than in a studio. This allowed Monet to directly observe and capture the transient effects of light and atmosphere in real time. His early works, such as Women in the Garden (1866–67), already showed his interest in light and nature, though they were met with criticism from the established art community.

Monet’s career reached a turning point in 1874 when he and his peers, tired of constant rejection from the official Salon, organized their own independent exhibition. It was here that Monet exhibited his now-famous painting Impression, Sunrise (Impression, Soleil Levant), depicting a hazy view of Le Havre’s harbor at dawn. The painting’s title—meant to convey a loose impression of a moment rather than a detailed representation—was mocked by a critic who coined the term “Impressionism” as an insult. Ironically, the name stuck and soon came to define an entire movement.

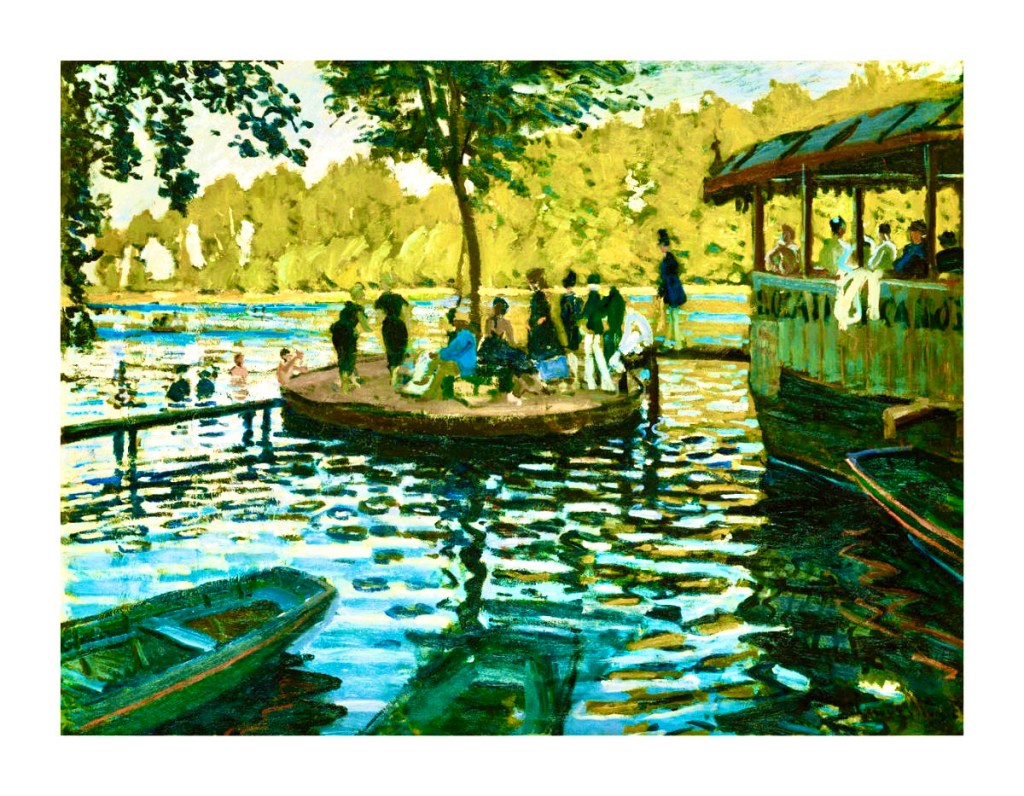

Despite poor reviews and limited commercial success in the beginning, the Impressionist exhibitions—held periodically over the next decade—gradually attracted attention and redefined public taste. Monet continued to innovate during this period, developing a distinctive style based on light, color, and natural forms. Paintings such as La Grenouillère (1869) and Camille Monet on a Garden Bench (1873) exemplify this approach.

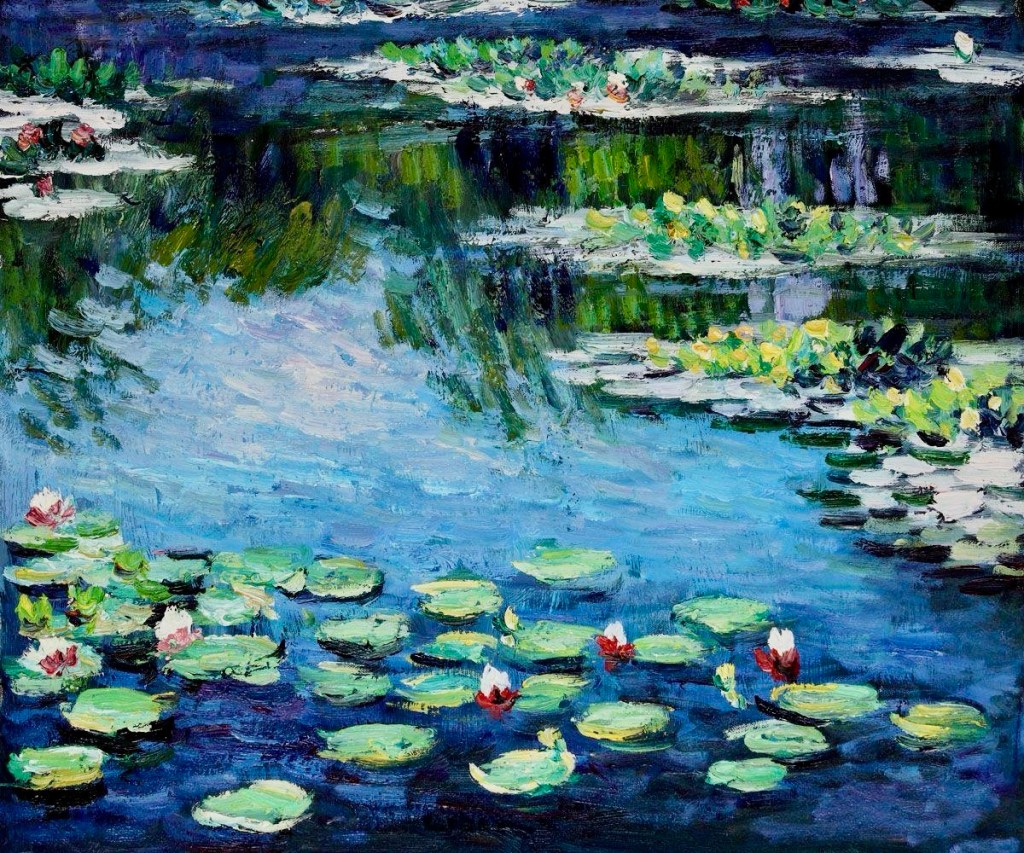

In 1883, Monet settled in the village of Giverny, where he would live and work for the rest of his life. There, he rented—and later purchased—a house with extensive gardens, which he carefully designed as both a personal retreat and a living canvas. He constructed a water garden, complete with a Japanese bridge and exotic plants, which became the central subject of his later masterpieces.

The inside of Monet’s house in Giverny is colorful and charming, reflecting his artistic taste. Each room is uniquely decorated, with bright walls, Japanese prints, and antique furniture. The drawing room salon was actually Monet’s first studio, and it became a shrine to the different periods of his artistic life.The yellow dining room and blue kitchen are especially striking, filled with warmth, natural light, and personal touches from Monet’s life. The kitchen features blue and white tiles, an array of copper pots and a large wood burning stove. Functional yet beautiful, the house reflects Monet’s love for harmony, comfort, and elegant simplicity in everyday living.

Monet’s water garden in Giverny was his artistic sanctuary, featuring a tranquil pond, water lilies, and the most photographed Japanese bridge. Inspired by Japanese prints, he carefully designed the water garden with exotic plants and flowing reflections. The ever-changing light and colors became central to his iconic Water Lilies series, blending nature and art beautifully.

Claude Monet’s life and work totally changed the art world. He was all about capturing fleeting moments, like how sunlight hits a flower or how fog blurs the edge of a building. He painted what he saw and how he felt in the moment, and it was honest and true to life. It wasn’t about any grand ideas, it was just about being in the present and enjoying the world around you. And that’s what really made his art so special.

Claude Monet died on December 5, 1926, at the age of 86. He was buried in a modest grave at the church cemetery in Giverny.

Monet approached cooking and eating with the same attention to detail and love for sensory experiences that defined his art. Whether tending his garden, planning a meal, or painting his famous water lilies, he valued everyday beauty and comfort. Food, for Monet, was not only nourishment but part of a joyful, full life—shared with family, friends, and fellow artists at his beloved home. The attached recipe, Monet’s Stuffed Tomatoes, reflects the ethereal approach with which he embraced life. Enjoy!

Leave a comment